By Brother Grimm

A poor widow once lived in a little cottage. In front of the cottage was a garden, in which were growing two rose trees; one of these bore white roses, and the other red.

She had two children, who resembled the rose trees. One was called Snow-White, and the other Rose-Red; and they were as religious and loving, busy and untiring, as any two children ever were.

Snow-White was more gentle, and quieter than her sister, who liked better skipping about the fields, seeking flowers, and catching summer birds; while Snow-White stayed at home with her mother, either helping her in her work, or, when that was done, reading aloud.

The two children had the greatest affection the one for the other. They were always seen hand in hand; and should Snow-White say to her sister, "We will never separate," the other would reply, "Not while we live," the mother adding, "That which one has, let her always share with the other."

They constantly ran together in the woods, collecting ripe berries; but not a single animal would have injured them; quite the reverse, they all felt the greatest esteem for the young creatures. The hare came to eat parsley from their hands, the deer grazed by their side, the stag bounded past them unheeding; the birds, likewise, did not stir from the bough, but sang in entire security. No mischance befell them; if benighted in the wood, they lay down on the moss to repose and sleep till the morning; and their mother was satisfied as to their safety, and felt no fear about them.

Once, when they had spent the night in the wood, and the bright sunrise awoke them, they saw a beautiful child, in a snow-white robe, shining like diamonds, sitting close to the spot where they had reposed. She arose when they opened their eyes, and looked kindly at them; but said no word, and passed from their sight into the wood. When the children looked around they saw they had been sleeping on the edge of a precipice, and would surely have fallen over if they had gone forward two steps further in the darkness. Their mother said the beautiful child must have been the angel who keeps watch over good children.

Snow-White and Rose-Red kept their mother's cottage so clean that it gave pleasure only to look in. In summer-time Rose-Red attended to the house, and every morning, before her mother awoke, placed by her bed a bouquet which had in it a rose from each of the rose-trees. In winter-time Snow-White set light to the fire, and put on the kettle, after polishing it until it was like gold for brightness. In the evening, when snow was falling, her mother would bid her bolt the door, and then, sitting by the hearth, the good widow would read aloud to them from a big book while the little girls were spinning. Close by them lay a lamb, and a white pigeon, with its head tucked under its wing, was on a perch behind.

One evening, as they were all sitting cosily together like this, there was a knock at the door, as if someone wished to come in.

"Make haste, Rose-Red!" said her mother; "open the door; it is surely some traveller seeking shelter." Rose-Red accordingly pulled back the bolt, expecting to see some poor man. But it was nothing of the kind; it was a bear, that thrust his big, black head in at the open door. Rose-Red cried out and sprang back, the lamb bleated, the dove fluttered her wings, and Snow-White hid herself behind her mother's bed. The bear began speaking, and said, "Do not be afraid; I will not do you any harm; I am half-frozen and would like to warm myself a little at your fire."

"Poor bear!" the mother replied; "come in and lie by the fire; only be careful that your hair is not burnt." Then she called Snow-White and Rose-Red, telling them that the bear was kind, and would not harm them. They came, as she bade them, and presently the lamb and the dove drew near also without fear.

"Children," begged the bear; "knock some of the snow off my coat." So they brought the broom and brushed the bear's coat quite clean.

After that he stretched himself out in front of the fire, and pleased himself by growling a little, only to show that he was happy and comfortable. Before long they were all quite good friends, and the children began to play with their unlooked-for visitor, pulling his thick fur, or placing their feet on his back, or rolling him over and over. Then they took a slender hazel-twig, using it upon his thick coat, and they laughed when he growled. The bear permitted them to amuse themselves in this way, only occasionally calling out, when it went a little too far, "Children, spare me an inch of life."

When it was night, and all were making ready to go to bed, the widow told the bear, "You may stay here and lie by the hearth, if you like, so that you will be sheltered from the cold and from the bad weather."

The offer was accepted, but when morning came, as the day broke in the east, the two children let him out, and over the snow he went back into the wood.

After this, every evening at the same time the bear came, lay by the fire, and allowed the children to play with him; so they became quite fond of their curious playmate, and the door was not ever bolted in the evening until he had appeared.

When spring-time came, and all around began to look green and bright, one morning the bear said to Snow-White, "Now I must leave you, and all the summer long I shall not be able to come back."

"Where, then, are you going, dear Bear?" asked Snow-White.

"I have to go to the woods to protect my treasure from the bad dwarfs. In winter-time, when the earth is frozen hard, they must remain underground, and cannot make their way through: but now that the sunshine has thawed the earth they can come to the surface, and whatever gets into their hands, or is brought to their caves, seldom, if ever, again sees daylight."

Snow-White was very sad when she said good-bye to the good-natured beast, and unfastened the door, that he might go; but in going out he was caught by a hook in the lintel, and a scrap of his fur being torn, Snow-White thought there was something shining like gold through the rent: but he went out so quickly that she could not feel certain what it was, and soon he was hidden among the trees.

One day the mother sent her children into the wood to pick up sticks. They found a big tree lying on the ground. It had been felled, and towards the roots they noticed something skipping and springing, which they could not make out, as it was sometimes hidden in the grasses. As they came nearer they could see it was a dwarf, with a shrivelled-up face and a snow-white beard an ell long. The beard was fixed in a gash in the tree trunk, and the tiny fellow was hopping to and fro, like a dog at the end of a string, but he could not manage to free himself. He stared at the children with his red, fiery eyes, and called out, "Why are you standing there? Can't you come and try to help me?"

"What were you doing, little fellow?" inquired Rose-Red.

"Stupid, inquisitive goose!" replied the dwarf; "I meant to split the trunk, so that I could chop it up for kitchen sticks; big logs would burn up the small quantity of food we cook, for people like us do not consume great heaps of food, as you heavy, greedy folk do. The bill-hook I had driven in, and soon I should have done what I required; but the tool suddenly sprang from the cleft, which so quickly shut up again that it caught my handsome white beard; and here I must stop, for I cannot set myself free. You stupid pale-faced creatures! You laugh, do you?"

In spite of the dwarf's bad temper, the girls took all possible pains to release the little man, but without avail, the beard could not be moved, it was wedged too tightly.

"I will run and get someone else," said Rose-Red.

"Idiot!" cried the dwarf. "Who would go and get more people? Already there are two too many. Can't you think of something better?"

"Don't be so impatient," said Snow-White. "I will try to think." She clapped her hands as if she had discovered a remedy, took out her scissors, and in a moment set the dwarf free by cutting off the end of his beard.

Immediately the dwarf felt that he was free he seized a sack full of gold that was hidden amongst the tree's roots, and, lifting it up, grumbled out, "Clumsy creatures, to cut off a bit of my beautiful beard, of which I am so proud! I leave the cuckoos to pay you for what you did." Saying this, he swung the sack across his shoulder, and went off, without even casting a glance at the children.

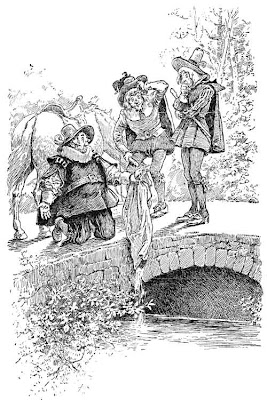

Not long afterwards the two sisters went to angle in the brook, meaning to catch fish for dinner. As they were drawing near the water they perceived something, looking like a large grasshopper, springing towards the stream, as if it were going in. They hurried up to see what it might be, and found that it was the dwarf. "Where are you going?" said Rose-Red. "Surely you will not jump into the water?"

"I'm not such a simpleton as that!" yelled the little man. "Don't you see that a wretch of a fish is pulling me in?"

The dwarf had been sitting angling from the side of the stream when, by ill-luck, the wind had entangled his beard in his line, and just afterwards a big fish taking the bait, the unamiable little fellow had not sufficient strength to pull it out; so the fish had the advantage, and was dragging the dwarf after it. Certainly, he caught at every stalk and spray near him, but that did not assist him greatly; he was forced to follow all the twistings of the fish, and was perpetually in danger of being drawn into the brook.

The girls arrived just in time. They caught hold of him firmly and endeavored to untwist his beard from the line, but in vain; they were too tightly entangled. There was nothing left but again to make use of the scissors; so they were taken out, and the tangled portion was cut off.

When the dwarf noticed what they were about, he exclaimed in a great rage, "Is this how you damage my beard? Not content with making it shorter before, you are now making it still smaller, and completely spoiling it. I shall not ever dare show my face to my friends. I wish you had missed your way before you took this road." Then he fetched a sack of pearls that lay among the rushes, and, not saying another word, hobbled off and disappeared behind a large stone.

Soon after this it chanced that the poor widow sent her children to the town to purchase cotton, needles, ribbon, and tape. The way to the town ran over a common, on which in every direction large masses of rocks were scattered about. The children's attention was soon attracted to a big bird that hovered in the air. They remarked that, after circling slowly for a time, and gradually getting nearer to the ground, it all of a sudden pounced down amongst a mass of rock. Instantly a heartrending cry reached their ears, and, running quickly to the place, they saw, with horror, that the eagle had seized their former acquaintance, the dwarf, and was just about to carry him off. The kind children did not hesitate for an instant. They took a firm hold of the little man, and strove so stoutly with the eagle for possession of his contemplated prey, that, after much rough treatment on both sides, the dwarf was left in the hands of his brave little friends, and the eagle took to flight.

As soon as the little man had in some measure recovered from his alarm, his small squeaky, cracked voice was heard saying, "Couldn't you have held me more gently? See my little coat; you have rent and damaged it in a fine manner, you clumsy, officious things!" Then he picked up a sack of jewels, and slipped out of sight behind a piece of rock.

The maidens by this time were quite used to his ungrateful, ungracious ways; so they took no notice of it, but went on their way, made their purchases, and then were ready to return to their happy home.

On their way back, suddenly, once more they ran across their dwarf friend. Upon a clear space he had turned out his sack of jewels, so that he could count and admire them, for he had not imagined that anybody would at so late an hour be coming across the common.

The setting sun was shining upon the brilliant stones, and their changing hues and sparkling rays caused the children to pause to admire them also.

"What are you gazing at?" cried the dwarf, at the same time becoming red with rage; "and what are you standing there for, making ugly faces?" It is probable that he might have proceeded in the same complimentary manner, but suddenly a great growl was heard near by them, and a big black bear joined the party. Up jumped the dwarf in extremest terror, but could not get to his hiding-place, the bear was too close to him; so he cried out in very evident anguish—

"Dear Mr. Bear, forgive me, I pray! I will render to you all my treasure. Just see those precious stones lying there! Grant me my life! What would you do with such an insignificant little fellow? You would not notice me between your teeth. See, though, those two children, they would be delicate morsels, and are as plump as partridges; I beg of you to take them, good Mr. Bear, and let me go!"

But the bear would not be moved by his speeches. He gave the ill-disposed creature a blow with his paw, and he lay lifeless on the ground.

Meanwhile the maidens were running away, making off for home as well as they could; but all of a sudden they were stopped by a well-known voice that called out, "Snow-White, Rose-Red, stay! Do not fear. I will accompany you."

The bear quickly came towards them, but, as he reached their side, suddenly the bear-skin slipped to the ground, and there before them was standing a handsome man, completely garmented in gold, who said—

"I am a king's son, who was enchanted by the wicked dwarf lying over there. He stole my treasure, and compelled me to roam the woods transformed into a big bear until his death should set me free. Therefore he has only received a well-deserved punishment."

Some time afterwards Snow-White married the Prince, and Rose-Red his brother.

They shared between them the enormous treasure which the dwarf had collected in his cave.

The old mother spent many happy years with her children.